The most clichéd, yet the most famous association that Bengalis have with Rajasthan is through Satyajit Ray’s movie ‘Sonar Kella’, shot on location in Rajasthan, particularly in Jaipur, Jodhpur, and Jaisalmer. Travel buffs from all over India, and especially Bengal, developed a special interest for Jaisalmer and its fort after watching this movie. For me, the romanticism of Rajasthan’s forts, havelis, and palaces, stories of kings and warriors, and love stories of the royals have been made sweeter and richer by the historical fictions of stalwart Bengali writers like Abanindranath Tagore – his stories of Chittorgarh in Raaj Kahini,, Saradindu Bandopadhyay – his short stories in the backdrop of Rajasthan’s forts and deserts, and of course Ray himself. Rajasthan became even more interesting for me owing to my maternal roots in Bikaner, which I had visited as a child with my parents.

It was naturally an exciting experience for me when I returned to Rajasthan for work many years later, sometime in 2006. Though the places I had seen in my younger days had drastically changed by that time, the childhood memories had remained freshly etched with adventurous and colourful images of historic architectures, deserts outlining the cities and villages, camel rides on the Thar, herds of peacocks, and the pebbled lanes of Jaisalmer full of quaint shops manned by local people in their colourful turbans.

More recently, I got the opportunity to visit and experience Rajasthan again, this time for work in western Rajasthan – the place of desert landscapes and desert communities. I had actually never met the indigenous rural music artists of this land before, except for perhaps a solemn looking musician playing at a Palace courtyard or a hotel lawn. My work took me to the folk musicians of these places, triggering memories of the sounds of the quintessential Kamaicha and Khartal used by Ray in Sonar Kella as early as 1974! I also got to see the temple of Ramdevra, a powerful local deity of Jaisalmer with many devotees, but more significant to me because of the important role that the Ramdevra railway station, located close to this temple, played in Sonar Kella.

The rural musicians we work with belong to the Muslim community and Mirasi caste and constitute communities of Langas, Manganiyars and Mirs. Their existence and music has been known to the world for decades as they have been performing with famous classical music Maestros as well for Bollywood. However, visits to their villages led to the realization that except a very few, these musicians still live in oblivion and are hardly known to the world or recognized as individual artists. But unlike many other indigenous performing art communities, they themselves have kept their tradition alive for generations, believing that music is fundamental to their ‘being’. Music has been their traditional livelihood for generations as they originally sang for their Jajmans (patrons) in return for money and gifts. A distinctive feature of this relationship between Jajmans and Mirasis, that continues till date, is the latter’s role as oral genealogists for the Jajmani families, some of them serving even the 14th or 15th generation of their Jajmans. With changing times and context, the Jajmani system and their customs became less elaborate and luxurious, leading to a decline in practice of many old songs and ballads. Simultaneously, some of these musicians stepped out of their villages to perform in more commercial public setups, and ended up travelling the world becoming famous, acclaimed and recognized by the global music world.

Though some of practices and styles differ between Langas and Manganiyars, they sing the same songs on different passages of life, seasons, daily life, epics, ballads, folklores, Gods and Goddesses, Pirs and Fakirs, Sufiyana Kalams, Bhajans and Qawwalis. Manganiyars play the iconic chordophonic instrument Kamaicha, along with Dhol, Khartal, Morchang, etc. The Langas play Sindhi Sarangi, Surnai, Algoza, Khartal, Morchang. As my assignment with banglanatak dot com is associated with revival and revitalization of traditional living heritages of India, a domain they specialize in, my visit was not only to learn about these musicians and their way of living but also to document, understand and accumulate knowledge on these folk artists and their music. My colleagues and I travelled after the COVID-19 lockdown, taking all precautionary measures for self-care. Our first field destination was a village called Barnawa Jageer located on the edge of Barmer desert, which is home to more than 200 Langa musicians. We stayed at a young artist’s house that had a large courtyard and a terrace that gave some respite from the summer nights. What was truly amazing was their hospitality and warmth, entwined with their music and songs. For the two days that we stayed there, our meals were arranged at the different artists’ places where we savoured their home cooked fresh food! During the day, other than interacting with these artists and their families, old and young, I also got the opportunity to enjoy a quick musical collaboration between two of my co-workers from Kolkata and the local young talents, leading to two 30 mins performances by two groups including a wide range of local traditional instruments, and vocals of different kinds. The distinctive sounds of Khartal, Morchang, Dhol, Sarangi, Been, Algoza, Matka playfully interacted with one another and the vocalists, creating a magical experience!

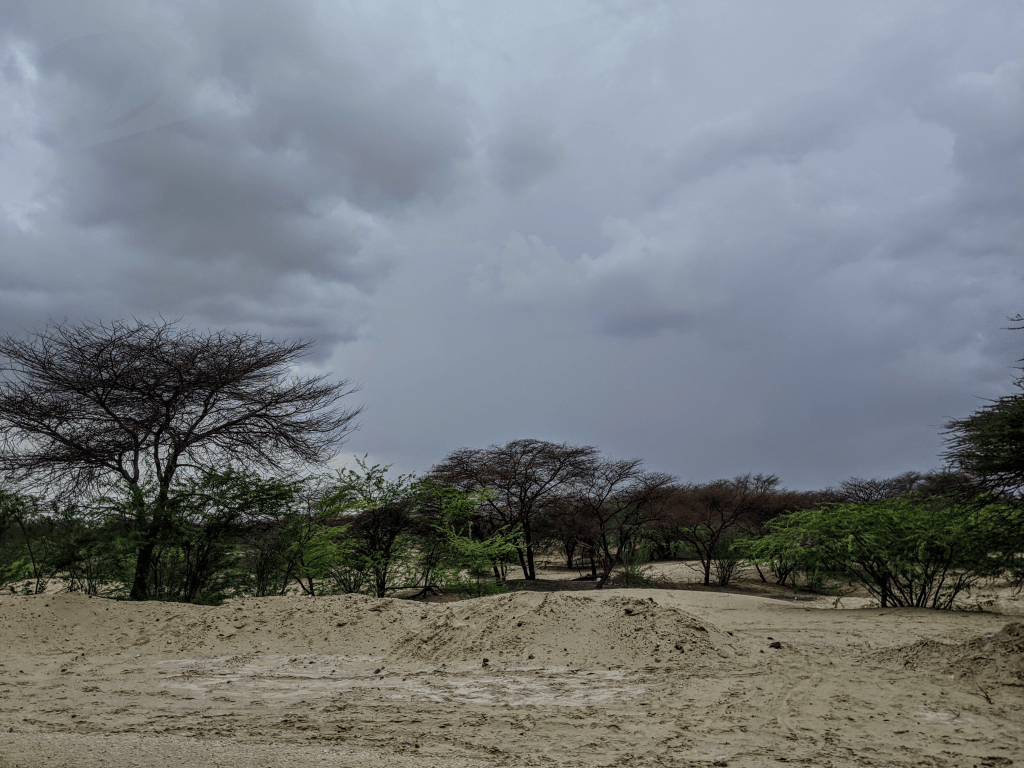

After a fulfilling stay at Barnawa Jageer, we headed towards Jaisalmer, making a brief halt at a place called Sheo – a hub of Manganiyar musicians. The legendary artists of that area had gathered to meet us at a music resource centre in Sheo. We entered an airy room where these senior musicians were seated, each in his own style of turban, jewellery, and distinguished demeanour. What was striking for me was not only the presence of so many doyens together, but also their exceptional humility and amiability that charmed us! Over many cups of tea, with dark clouds in the sky and cool wind rushing past us through the windows, we listened to their stories, challenges and aspirations for a flourishing future of their dying traditions, along with beautiful articulations from their Kamaicha, Been and Khartal. The legendary singer Bade Gazi Khan, who became word famous much before our times, sang two of his famous numbers in his usual ways of matching bodily actions and expressions along with lyrics, hypnotic eye contact with audience, making it a brilliant theatrical rendition of his songs! I had never seen anything like that before.

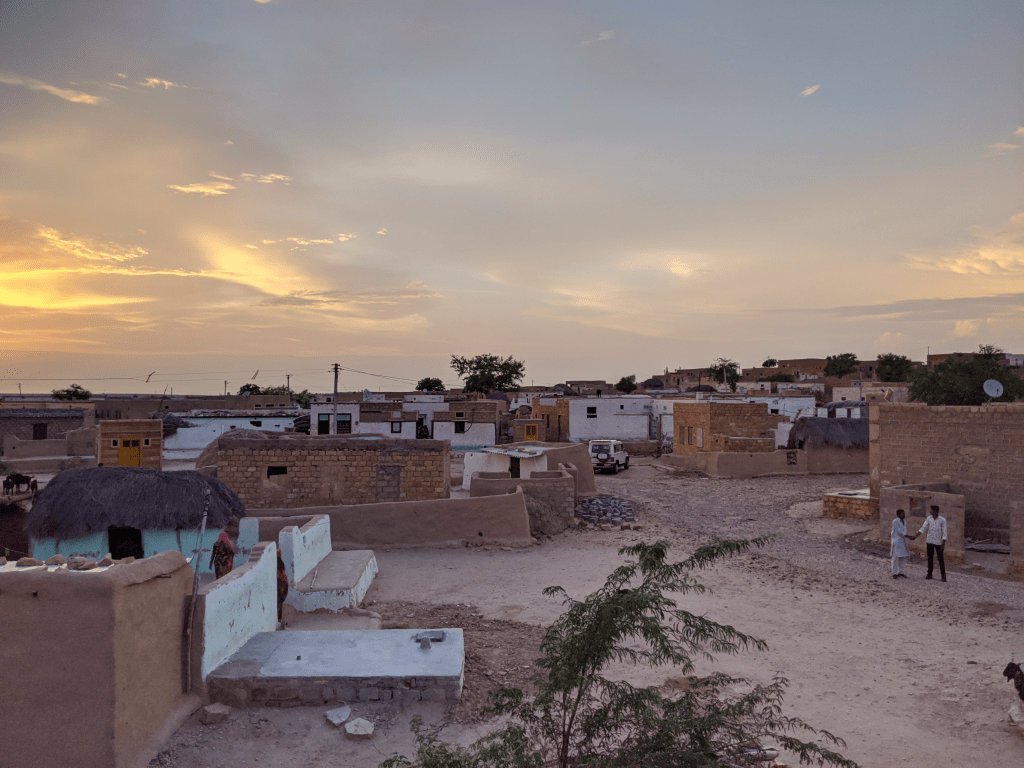

Later that evening, we reached a small village called Barna located in the middle of Jaisalmer desert. Once again our place of stay was another young artist’s house who pleasantly welcomed us by saying, “Aapi ka ghar hay”. He was a young chap in his twenties, and already a renowned musician. It was a large traditional house with more open spaces than covered rooms, which was a delight, especially coming from cities. The main gate of the house led to a narrow open space that had a small flight of stairs leading to a spacious and well stretched frontal porch. On either side of the porch were two rooms, with doors opening to the porch, which we occupied. In the centre of the porch was a low wooden gate that opened to a huge courtyard with rooms around and a staircase to the terrace. We stayed in this house for the next four days, working during the day at a next door resource centre, and enjoying evening jamborees of free flowing soulful music, adda, full moon, clear skies and cool breeze. As much as it sounds attractive, it was also excessively hot and our team of six slept in the Khatiyas on the porch under the moonlit sky every night, wishing sometimes to have a way to dim the moon a little!

My work there involved interacting with highly acclaimed Master artists and Award winners of Langas and Manganiyars together (aged between 40-80 years), documenting socio economic aspects, cultural significance, traditional practices, and oral histories of their musical heritage. It was indeed an engrossing experience to learn about them, and they left us in wonderment of their huge repertoire and diversity of songs, all of which they remembered by heart and only through oral transmissions. To our elation, in this group of senior artists, we also met the son and nephew of the folk artists who were featured in Sonar Kella, the Kamaicha player Late Shri Ramjan Hamu Khan and the legendary Khartal player, Late Shri Saddik Khan, shown playing at Ramdevra station. We heard from them their childhood memories of Ray’s visit to their village, where the scene was actually shot! Adding to this opulent folk heritage were innumerable folk tales on their local deities and devis, pirs and fakirs, heaven and earth, gods and demons, heroic fables, good and evil, sagas from epics, love stories, and so on, that can surely inspire many a novelist. For every story or explanation, they had a song to sing, truly diffusing the lines between our work and enjoyment. Often the small children and young boys of the village would gather inside the room to listen to the elderly and take a slice of this experience which must have been unique for them!

As I write this piece, I realize that my experiences are still sinking in, making precious memories especially in the times of COVID-19, when the world around is so grim. During our stays in these villages with these artists, I did forget at times about the fear and dismay that has grasped the world. It may be because they sang about birth and life, about goodness and blessings; about loved ones who are waiting to return to each other, about calling the almighty who exists everywhere and is the world’s saviour. They narrated the power of the Almighty which manifests in nature, in words such as: “Har dil mein basta tu, har rang me tu hi tu…”. Some of them had also expressed their emotions as “humein lag raha hai hamare sath koi hai”, “sannata nehi hai”, “jhum gaye sab”. According to them, music is giving them the strength and encouragement to not lose hope in these difficult times. They worship their music which gives them collective power, strength and faith to fight hardships on one hand, and derive immense joy from living on the other. My fondness for Rajasthan would have remained incomplete, even with the brilliant and elite array of literary and creative gems, had I not known about these amazing rural musicians and beautiful people! The richness of their cultural capital is known to the world, but how it builds their emotional capital was worth learning about.

Brilliantly narrated and well scripted. Keep writing!

LikeLike